| Shop |

- Academy

- Studies

- Courses

- – Courses 2024

- – All courses

- – Painting

- – Drawing

- – Printmaking

- – Photography / Film / Video

- – Sculpture

- – Installation

- – Performance

- – Architecture

- – Art Critique / Writing

- – Curating

- – Course archive 2023

- – Course archive 2022

- – Course archive 2021

- – Course archive 2020

- – Course archive 2019

- – Course archive 2018

- – Courses until 2017

- Events

- Blog/Videos

- Press

On Reappropriation

When I slipped into Eli Cortiñas’ class on Tuesday afternoon, most of her students were squirreled away behind laptops, headphones on, clicking away. Others were standing at trestle tables, sifting through clippings on a search for coherency. The students worked in pin-drop silence, and I cringed at the sound of my heels on the floorboards. I found a seat at the back of the room. Assisted by Elina Saalfeld, the Spanish-Cuban montage artist is teaching “Context is everything, montage too” a two week course exploring how montage can be used as a critical tool, as a means of asking questions, and a narrative device. One student described the techniques of montage and collage as being “super nostalgic”. It is after all, an art form in which we reorder memories and histories from preexisting materials, in this case video, to tell new stories.

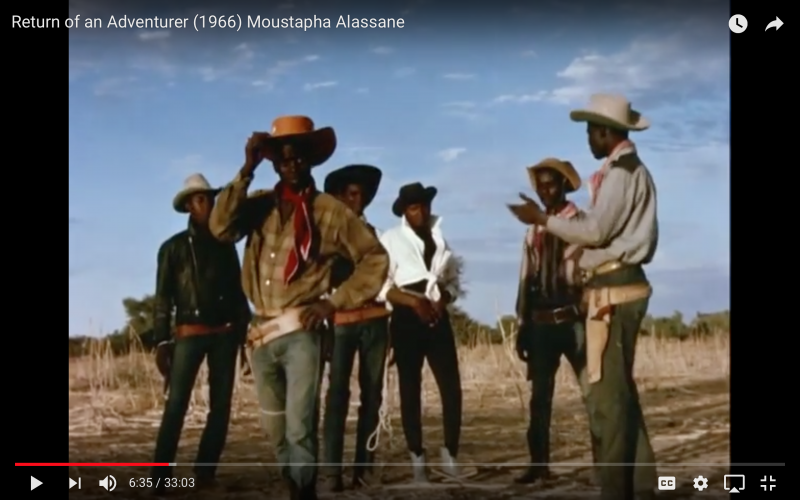

Alice Bucknall’s collage

“I have major beef with brutalism”, confessed Alice Bucknall, an American-born writer and student, as she prepared to present her work to the class. Their task was to create a collaged image exploring a matter of their choice using Cortiñas’ own paper materials. Bucknall’s collage, a towering column of images sourced from two magazines—one she would naturally gravitate towards, and another she’d usually be disinterested in—criticizes the hypermasculine tones of brutalism through the reappropriation of phallic symbols. Her collage is almost sculptural, its position is precarious and exciting. A woman in pink—a maximalist—falls spreadeagled towards the tower. The two young girls in the bottom left face the chaos, standing on a snake with nonchalance. Bucknall explained that during her initial consideration of how to reconstruct her chosen images, she wanted to use the snake to refer to the fable of Adam and Eve. In the final composition, the snake alludes instead to a historically controversial symbol of American patriotism: the Gadsden Flag. “DONT TREAD ON ME”, reads the yellow flag: a coiled rattlesnake prepares to strike. On only the second day of the course, the students meditate on an array of matters: the climate crisis, race relations, heteronormativity and the colonisation of bodies to name a few.

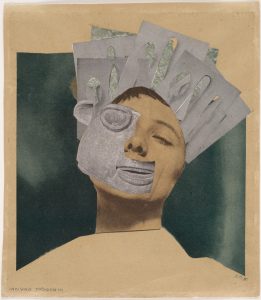

Indische Tänzerin: Aus einem ethnographischen Museum (Höch, 1930. MoMA)

Eli Cortiñas cares deeply about montage, she loves it, in fact. Years of sifting through colossal amounts of footage during her time working as a documentary film editor prepared her for an artistic practice primarily involved with the tradition of appropriating video to reconstruct identities, form narratives and ask questions. She is enamoured by the work of Hannah Höch (1889-1978), the German Dada artist whose photomontage series From An Ethnographic Museum (1930) readily criticized the attitude post-World War I Germany had towards its former colonies. Höch’s candid honesty directly influenced Cortiñas—both From An Ethnographic Museum and The most given of givens (2016), a film screened by Cortiñas during her artist talk at Galerie 5020 leave us no choice but to consider the often perverse and misleading Western gaze. “Visual montage is not only about telling stories in space, but also in time.” she explained.

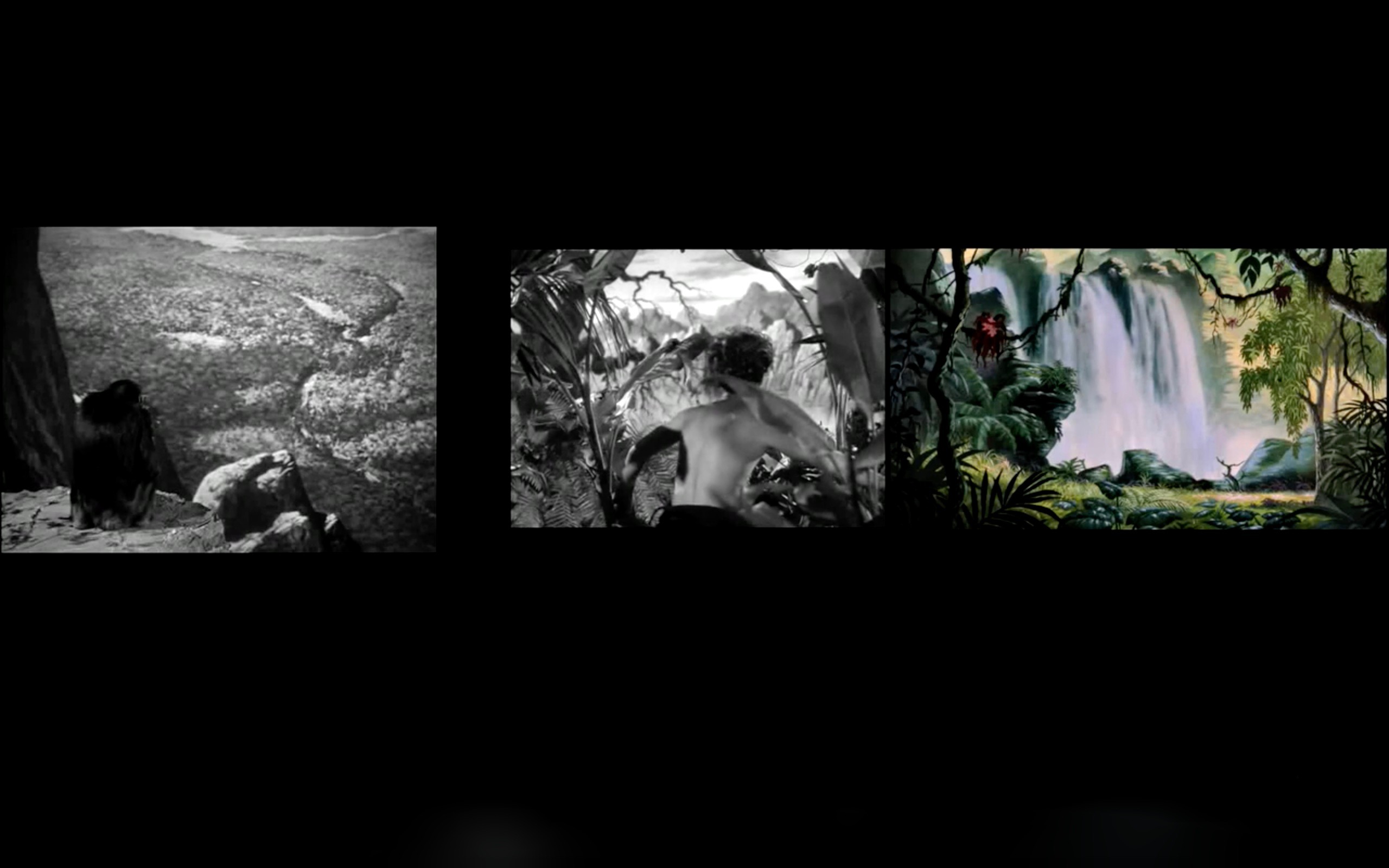

Just as Höch combined images of contemporary Western women with archival non-Western images, The Most Given of Givens, pits footage from early and more contemporary Western films about the non-Western world, against the work of pioneering non-Western filmmakers. The contrast forces us to consider the long standing tradition of otherment in Western film, as we reflect on the images before us. The three-channel work makes clear that montage is a cyclical art form, manipulating time and history to tell new truths.

Cortiñas’ film included clips from Tarzan the Ape Man (1932), in which we see American explorers interacting with an unnamed local sub-Saharan people. The Americans move laterally, observing the dancing group, whom they never actually met—the footage for this repeated sequence was collected on-site by a second unit before being projected in a Hollywood studio. Watching the actors interact with this projection is not only visually jarring, it is a direct othering. By juxtaposing this footage with clips from the many Tarzan films made in the 1940s, Avatar (2009) and The Jungle Book (1993) among other titles, the audience is invited to reflect on the ethnographic quality of these films and how they, over the course of history, repeatedly place distance between the Western man and the other.

The Most Given of Givens (Cortiñas, 2016)

The Most Given Of Givens also introduced me to the work of Nigerien filmmaker Moustapha Alassane. It includes moments from his 1966 pop art film, Le Retour d’un aventurier (The Return of an Adventurer), which delves into the tenets of African mimicry and post-colonialism, free from the constraints of the Western gaze.

It is a West African Western: a young man returns to Niger from America, with him he brings the mindset of a cowboy, as well as clothes for his friends. Chaos ensues. As the black cowboys assume their new identities, panic, brawls and robberies plague the village. Alassane’s film demonstrates the results of the imposition of North American values on an Nigerien village using the (black) cowboy as a focal object.

Shepherding is a profession as old as time, yet the cowboy and his genre—the Western—symbols of expansion, bravery, white masculinity and the taming of virgin land dominated early American cinema. He still exists today as a trademark of American optimism, and by reappropriating this symbol, Alassane prompts us to ask how the cowboy and the Western are transfigured when placed in a context so foreign, so other. The film is tongue-in-cheek, but we must remind ourselves of the calibre of media being consumed by young West Africans at the time. We view the black cowboy as ridiculous, it doesn’t seem to make sense, but how ridiculous is the adventurer epic, filmed against a projection of an exoticised, unnamed and unvisited country? By using elements of this film amongst stratified examples of Western ethnographic films that both directly and indirectly sought to other the African body and its habitat, Cortiñas provokes us further. The Most Given of Givens demands the initiation of a conversation about the decolonisation of film.

Le Retour d’un aventurier (Alassane, 1966)

One must note that Cortiñas’ work is unnarrated. Any words spoken are recycled from the films dissected. We began to discuss Lev Kuleshov, a Soviet filmmaker who was active at the beginning of the 20th Century, and for whom the following principle is named: the viewer of a film will derive more meaning from the interaction between two consecutive clips than one of those clips in isolation. As we discussed the Kuleshov effect, I was reminded of the work of Arthur Jafa, namely APEX (2013) and Love is the message, the message is death (2016). I recalled a moment during a screening of his work, when the film moved from a clip of a gospel singer hypnotised in the throes of praise, to a clip of a man lamenting the loss of his son at the hands of police. The singer and father—both black—though emotionally unrelated, shared the same expression, a coincidence Jafa capitalised upon. My mind raced with thoughts on pentecostalism, the black joy-suffering paradigm, and the relationship between African Americans and the police, all in a split second.

The first time I asked Eli Cortiñas’ about her ten year hiatus from shooting her own material, she laughed. We moved onto the next question, but I was too intrigued. I asked again. “I always felt that I could never properly catalyse my own ideas. When I worked as a documentary film editor, I learned so much about how to use what has already been created, how to use collective memory. I just felt that it was the most natural thing to do, to work with pre-existing work.” Cortiñas’ work wants us to assess morality and query social norms through the carefully considered combination of directly and indirectly related sources. Whilst collage remains confined to the tradition of paper, video montage and the ever growing resources at our disposal invite us to rewrite the future, using our histories.

Selection of work from Cortiñas and Saalfeld’s students

- 22 August 2019

Authors

- Adelaide D' Esposito

- Albatross on the fortress

- Benedikt Breinbauer

- Chloe Stead

- Collaborative lecture performance

- Everything you always wanted to know about curating

- Gaia Tovaglia

- Hildegund Amanshauser

- Hili Perlson

- Karin Buchauer

- Montage my beautiful trouble

- Nina Prader

- Olamiju Fajemisin

- Processing our days

- Recently deleted

- Summer Academy

- Tex Rubinowitz

- Writing in on and through art

List by

Internationale

Sommerakademie

für bildende Kunst

Salzburg

T +43 662 842113

| Follow us: Newsletter TikTok YouTube |

| © 2023 / Imprint / Privacy Policy |